Douglas Whalin late antique historian

‘Pagan’ classics, Christians, and a Late Antique world-mountain

The following appeared as a guest-post for the Mountains in the Classical Tradition Blog, part of a Leverhulme-supported research project by Jason König and Dawn Hollis, members of the School of Classics at the University of St Andrews. My thanks to both of them for the opportunity to share a bit of Late Antiquity with a wider audience.

The mountains of Greece and the Aegean connect us as much with Classical Antiquity as with other points in time. A tourist visiting Sparta will find Mt. Taygetos dominating the southern horizon just as it did in the early fourth century BC when the city was the hegemon of all of Greece. But in visiting its hillside, the tourist can equally find bronze-age Mycenean tombs as well as the medieval city (and UNESCO World Heritage Site) of Mystras. In both the real world and in the literary imagination, mountains provide a canvas on which we can track how societies carry out an ever-ongoing conversation with and about their cultural heritage. This is certainly true of the period in which my research specializes, Late Antiquity.

Late Antiquity (approximately the fourth through seventh centuries AD) saw Christianity rapidly expand to become the dominant religious group across the Mediterranean world. Christians lived alongside non-Christians, and both groups engaged one another about the relationship between – or irreconcilability of – Christianity and the literary/cultural tradition inherited from Ancient Greece. Greek-speaking Christians still lived in once-‘pagan’ urban spaces; the literate elite read, admired, emulated, and transmitted on the ‘pagan’ classics to future generations; and saints performed miracles in a countryside still dotted with ‘pagan’ mountain-top shrines. The process of reconciling a new faith with an established cultural tradition played out in the use of space, the forms of architecture, the structure of social hierarchies, the content of education, and, of course, the literary treatment of mountains.

Before going on, a quick note on terminology is necessary to contextualize a large and complex historical issue, and explain why Christian concern for ‘paganism’ was partially a debate about the inheritance and transmission of classical culture. The English word ‘pagan’ comes from Latin, paganus, which could be translated as ‘rustic’ or ‘bumpkin,’ but our Latin-derived terminology obscures all that’s going on with this concept. In Greek – the common language of St Paul and the early Church Fathers as much as of Homer and Aristotle – the signifier for ‘pagan’ was Ἕλλην/hellene. This word means ‘Greek’ as much with respect to language as culture, education, and world-view. As paganus implicates the ill-informed superstition and the practice of the common folk, hellene implicates a learned and official religion and culture, in other words our ‘classical tradition.’

The struggle to reconcile Christian and pre-Christian traditions and knowledge occurred across the breadth of literary genres, including the ‘sciences’ of astrology and astronomy, branches of natural philosophy which were undifferentiated at this time (Bernard 2018). For Kosmas Indicopleustes, who wrote the Christian Topography in the sixth century, the ‘pagan’ works on the earth and the sky clearly contradicted the Bible. Kosmas composed an alternative, Christian model for the world based on his reading of the Old Testament. For Kosmas, mountains were core structures for explaining the relationship between and functions of the earth and the celestial bodies. Rejecting the Ptolemaic model, which placed earth as the centremost of a series of cosmic spheres, Kosmas proposed a flat-earth model based on biblical descriptions.

Ἡ γῆ μὲν πᾶσα τετράγωνός ἐστι, καθὰ προεγράφη. Τὸ ἀνάστημα δὲ αὐτῆς τῆς μεσοτάτης καὶ τὰ ὕψη τὰ κατὰ βόρεια καὶ δυτικὰ μέρη ἐσημάναμεν ἐνταῦθα διαγράψαντες ὅπως, μέση τυγχάνουσα καὶ πέριξ ἔχουσα τὸν Ὠκεανὸν καὶ πάλιν πέριξ τὴν ἄντικρυς γῆν, τῶν ἄστρων κυκλευόντων αὐτήν, δύναται καὶ κῶνον ἀποτελεῖν τὴν σκιὰν κατὰ τοὺς ἔξω, καὶ ὅτι καὶ κατὰ τὸ σχῆμα τοῦτο δύνανται καὶ αἱ ἐκλείψεις τῆς σελήνης ἀποτελεῖσθαι καὶ νύκτες καὶ ἡμέραι, καὶ ἡ θεία Γραφὴ μᾶλλον ἀληθεύει λέγουσα· «Ἀνατέλλει ὁ ἥλιος καὶ δύνει ὁ ἥλιος καὶ εἰς τὸν τόπον αὐτοῦ ἕλκει· ἀνατέλλων αὐτὸς ἐκεῖ πορεύεται πρὸς νότον καὶ κυκλοῖ πρὸς βορρᾶν· κυκλοῖ κυκλῶν, καὶ ἐπὶ κύκλους αὐτοῦ ἐπιστρέφει τὸ πνεῦμα», ὡσανεὶ τὸν ἀέρα κυκλεύων πάλιν εἰς τὸν τόπον αὐτοῦ ἐπανήκει.

The whole world is a square, as I wrote previously. The highest part of its middle and the summit, namely the north and the western part, we have marked here, being drawn out exactly so. The middle is situated here with the ocean all around, and around that in turn an opposite shore, with the stars encircling it. The cone is able to produce a shadow toward those outside it, and thus, according to this scheme, it is able to produce the eclipses of the moon and night and day. What’s more, divine scripture attests this truth, saying: ‘The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises. The wind blows to the south and turns to the north; round and round it goes, ever returning on its course,’ [Eccl. 1, 5-6] the air, as it were, circling back into the place where it returns. Kosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography, IV.11. Ed. Wolska-Conus 1968, 550-551. Trans. by me.

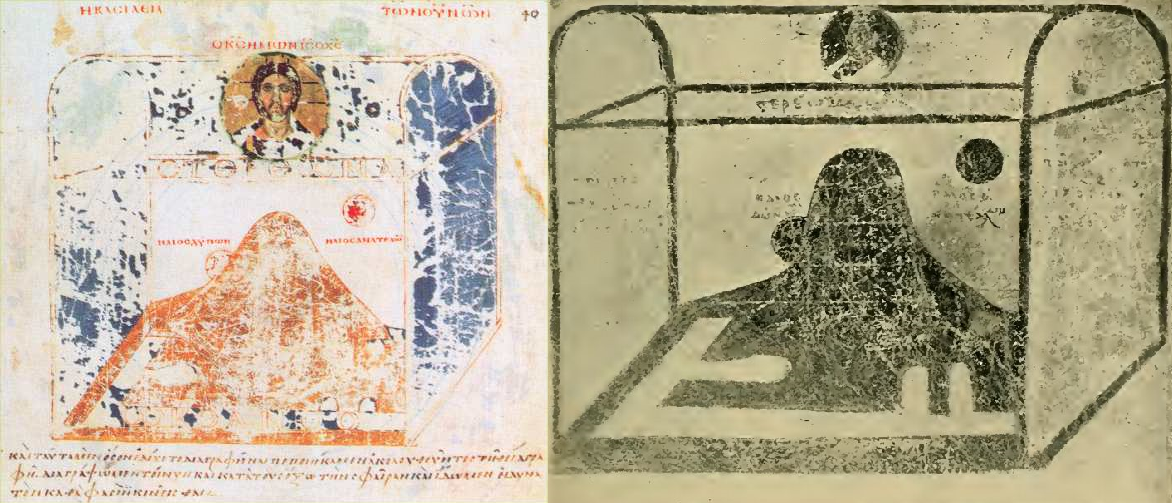

Two versions of Kosmas’ tabernacle. The stylized coast of the Mediterranean at the foot of the word-mountain can be seen in both, although it is easier to make out in the black-and-white version. The colour illustration, from Vat.Gr.699, allows us to more clearly make out the sun, labelled ἥλιος, which is depicted twice in the sky behind the mountain.

Two versions of Kosmas’ tabernacle. The stylized coast of the Mediterranean at the foot of the word-mountain can be seen in both, although it is easier to make out in the black-and-white version. The colour illustration, from Vat.Gr.699, allows us to more clearly make out the sun, labelled ἥλιος, which is depicted twice in the sky behind the mountain.

Illustrations like this one accompany Kosmas’ work in manuscripts, such as the ninth-century example digitised by the Vatican Library Vat.Gr.699, and certainly help make sense of what he was attempting to describe. Kosmas based his model [schema] on a devout and strict literalist reading of scripture, all of creation was literally a mountain, with days and nights created by the sun being obscured by its summit.

His model places the ‘inhabited world’ [oikoumene] of the Eurasian and African continents at the base of a massive cone, around which lies the Ocean, the body of water which the ancients knew surrounded the land. Kosmas’ mountain rose into a heavenly tabernacle – a box, basically, made up of the sky and celestial objects like the sun, moon and planets.

If you find it hard to imagine how anyone could be persuaded by this idea, don’t worry, neither could most of Kosmas’ contemporaries. It should be made clear here that Kosmas’ view was comprehensively rejected even in his own time, and received scathing rebuke from contemporary and later philosophers and theologians alike, who overwhelmingly accepted that the earth was spherical throughout the middle ages (Lindberg 2007. Villey 2014, 122-123). Even the illustrator of Vat.Gr.699 included a picture of the Ptolemaic spherical model alongside Kosmas’ tabernacle.

Reading Kosmas in the context of a workshop inspired, at least nominally, by the half-centenary of Nicholson’s Mountain Gloom Mountain Glory proves to be an interesting test case. If ‘glory’ characterizes the ancient Greek (that is, Hellenic) view of mountains, and was recovered after the Renaissance by reconnecting with their authentic cultural vision, then ‘gloom’ is, in its way, anti-classical, a rejection of that Hellenic inheritance. If we’re expecting to find ‘mountain gloom’ as an opposition to a classically-inspired ‘mountain glory,’ surely a Late Antique Christian who radically rejected ‘pagan’ learning should be a good place to start?

Maybe not so much, it turns out. In the first place, the widespread rejection of Kosmas’ tabernacle-model among even his fellow Christians helps to illustrate how Late Antique process of Christianization was not a broad social rejection of everything classical but one of adaptation and reconciliation of cultural forms, attitudes, and truths from the ‘pagan’ and Biblical traditions. Second, Kosmas’ model points to a degree of anti-classical comfort with mountains – at least in the abstract. After all, Kosmas understood that his world-mountain was created by God, and a divinely ordered plan can hardly be too bad.

Works cited

- Bernard, A. (2018) ‘Greek Mathematics and Astronomy in Late Antiquity’, in P. T. Keyser, J. Scarborough, and A. Bernard (eds) Oxford Handbook of Science and Medicine in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kosmas Indicopleustes (1968) Topográphie chrétienne. Edited by W. Wolska-Conus. Paris: Éditions du Cerf (Sources chrétiennes; 141).

- Lindberg, D. C. (2007) The beginnings of western science: the European scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context, prehistory to A.D. 1450. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Villey, É. (2014) Les sciences en syriaque. Paris: Geuthner (Études syriaques; 11).

Images from Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons Public Domain

March 27th, 2020 by DC Whalin