Douglas Whalin late antique historian

Contribution to Realism in Hagiography workshop

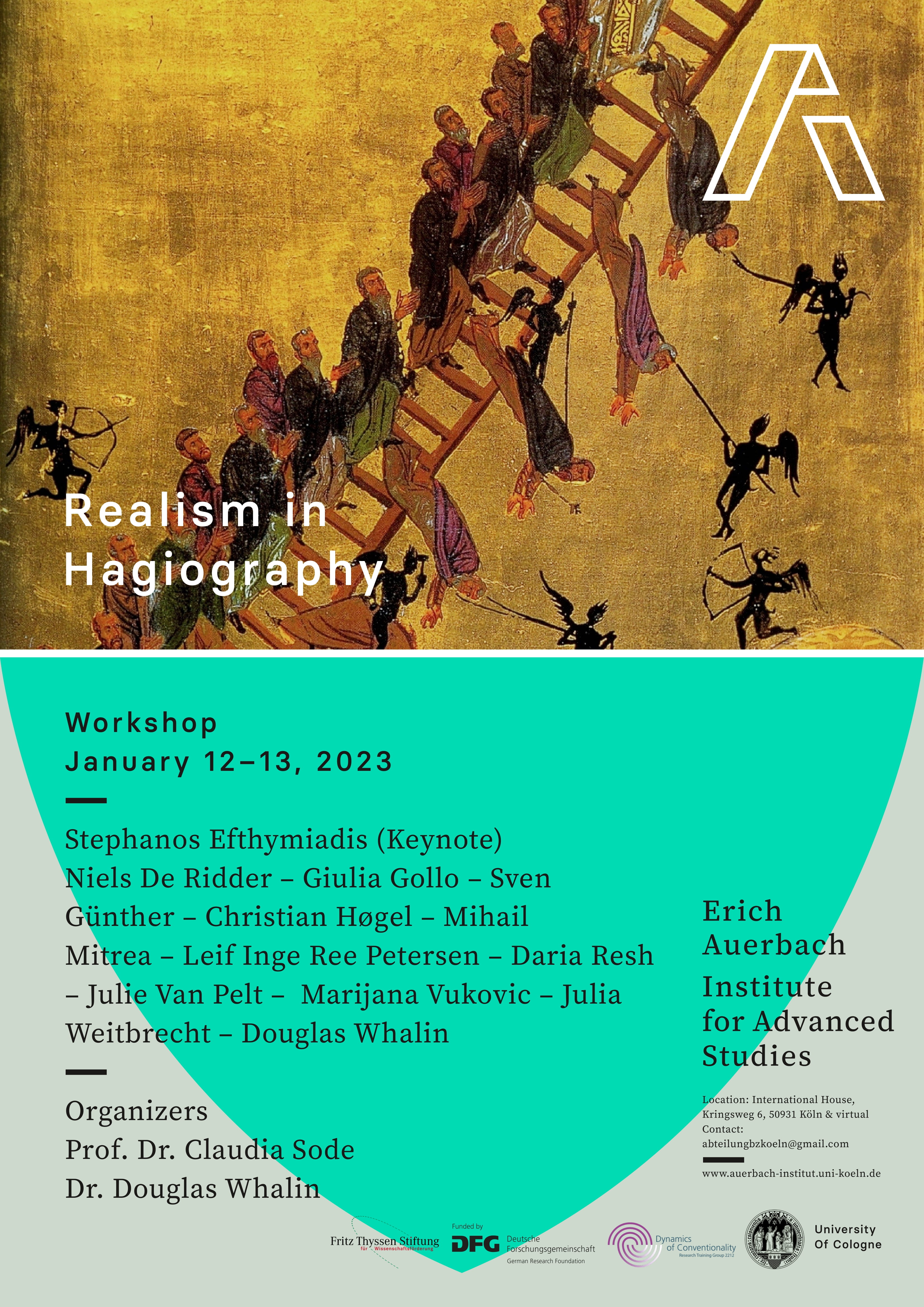

With Prof. Dr. Claudia Sode I co-hosted the international workshop ‘Realism in Hagiography’ earlier this month, on 12-13 January 2023. The format was hybrid, meeting both in-person at the University’s International House and online. We were both very pleased with how the event worked, and hope that everyone who joined us had as lovely a time as we did!

Claudia and I are also pleased to announce that we will be publishing the proceedings of the workshop. We are partnering with the Journal of Ancient Civilizations Supplementary Series. This continues the project’s international collaborative partnership between the University of Cologne and the Institute for the History of Ancient Civilizations (IHAC). Claudia was a co-editor for a previous volume with them, and this will be the first project to which I will contribute as a volume editor.

In addition to organizing the workshop I also contributed a paper which was part of the workshop’s first session. A plain text version of my draft contribution is follows.

Miraculous realist landscapes in Late Antique Syria

The vitae of Symeon Stylites the Elder (circa AD 390—459) form a group of texts which is very specific with respect to space and time. It is replete with factual details (πράγματα), some of which were or still are independently verifiable. The setting was integral to the function of a saint’s vita as not only an exemplary tale about a person who should be admired and emulated but also a persuasive treatise, one which sought to convince believers of the veracity (ἀλήθεια) of the spiritually beneficial tale. The specificity of Symeon’s stories places emphasis on the locality of his cult, grounding it within the physical landscape, the social landscape, and specific relics assembled at his cult site. Truth does not necessarily lie in the factual specificity but arises from the degree to which these stories fit within the mental world of storytellers and audience alike.

This paper begins by exploring a specific passage, a story about a lion miraculously defeated by Saint Symeon, and explores what it can tell us about the relationship between the emergent saint’s cult and the world around it. It will then examine a few other texts from neighbouring times, spaces and genres, looking more broadly for parallels and exceptions. In problematizing the relationship between specificity and narrative the goal is to explore the question, wherein lies the veracity of these types of textual sources?

The miracle of the lion of Ukkama

The following is an excerpt from the Syriac vita of Symeon Stylites which tells of a miracle performed on a lion on Mount Ukkama.

Again in another time a fierce lion was seen on Mount Ukkama (Black Mountain). A lion had never been seen there before. It devoured and cruelly ravaged people. It ate and mangled an innumerable crowd. Travel was disrupted, for no one dared for fear to pass beyond the door of his house, either to go to work or to travel. In one day it could appear in many places. News of it reached the cities, the prefects also heard it and sent hunters and soldiers and Isaurians armed with spears and swords. But no one did him any harm at all. He was not scared by a crowd, but many people trembled and were afraid when he roared. After he had so ravaged for a long time, a great crowd from the north gathered and came and told the saying, ‘He enters sheepfolds and houses; he leaves the wild animals alone and eats people.’ When the saint learnt how he had ravaged and how many people he had destroyed, he said, ‘I trust my Lord Jesus Christ that he will never again destroy the form of man. In the name of Christ take some of this hnana and oil. Wherever you see him—whether lying down or standing up—make crosses on all sides. Behold, the angel of the Lord will smit and paralyze him.’ Then our divine Lord worked this favour for him publicly. For as they went along they spotted him crouching before them on the road. When he saw then, he leapt up in his usual manner and they on seeing it trembled and were afraid. He was about to attack them when he trembled, shuddered, and fell. They recognized that his wound was from the Lord and one of them drew his spear, went up close and struck him in his heart and killed him. They skinned him and brought the skin to the enclosure. While they all gave thanks exceedingly and praised our lord, for the devastation had been evil and cruel. (tr. Doran 1992, 167-8)

The miracles in the Syriac vita are arranged thematically (not strictly chronologically), and the story of the lion of Ukkama appears among other set in the countryside near Symeon’s enclosure near the village of Telneshe (ܬܠܢܫܐ). Like many other miracles, it is partly performed by Symeon who gives instructions for a ritual to defeat the beast, and partly performed by an unnamed party of believers who witness the miracle (the lion becoming paralyzed) and confirm it (slaying the lion and bringing its pelt to Symeon’s enclosure). The wonderous truth – a lion was miraculously paralyzed allowing it to be killed – is told with reference to: specific spaces (Mount Ukkama, Symeon’s enclosure); people (civil officials, Isaurian foederati from mountains north of Cilicia); actions (direct speech, specific ritual instructions); and even physical object (the lion’s pelt). The reference to specific factual details (τὰ πράγματα)—which believers can independently perceive, experience or verify—attests to the truth (ἡ ἀλήθεια) of the story as a whole. In practical terms, we can surmise that it was possible for a pilgrim to visit Symeon’s sanctuary at Telneshe and see the pelt or travel to Mount Ukkama and ask local residents about whether there had been a lion there, thereby confirming the miraculous truth.

Yet as one progresses from specific observations about this passage towards interrogating it as a historical source, interpretational problems appear and compound. Assuming that there was indeed a lion’s pelt on display at Symeon’s enclosure, what made this story believable as an explanation for its origin? The narrative is completely devoid of specifics about the group of people who witnessed the miracle and brought proof of it back to the compound. It provides the reader minimal orientation with respect to social networks of Symeon’s world. Is a lion terrorizing a region a cause of fear because it is a frequent occurrence in different regions of the Syrian massif or altogether exceptional? Or is it the severity and the fact that it attacked people which is exceptional? If the facts of the vignette are ambiguous, the explicit articulation of violent details highlights the fear of such situation and concern over a community’s preparedness to deal with it. Regardless of the historical factualness of the events it describes, the miracle of the lion of Ukkama realistically reflects the thought-world of people living in the mountains of fifth-century Syria, quintessentially marginal spaces both economically and socially within the context of the Late Antique Roman world.

The vitae of Symeon Stylites the Elder

By the beginning of the fifth century AD when the historical Symeon came of age, Christian ascetic practices, whose origins are traditionally associated with Egypt in the late-third to early-fourth centuries, had been established in Palestine and Syria for more than a generation. Both solitary (eremitic) and communal (coenobitic) ascetic forms were practiced among pious Christians. So while Symeon’s asceticism was not new, the specific form he practiced was. He was the first Christian ascetic to dwell atop a pillar (a στῦλος, hence ‘stylite’). Even before he began doing this, all surviving accounts agree that he practiced forms of self-mortification which were unprecedented, disconcerting, and even polarizing in his own day.

There are three independent textual traditions for the life of Symeon Stylites, all composed within living memory of the holy man’s life. The Syriac vita, from which the miracle of the lion of Ukkama is drawn, is the longest as well as the latest. It is dated by colophon note to AD 473 around the time of the construction of the great church around Symeon’s column, only fourteen years after his death in 459. The text was edited in 1748 and both German and English translations are principally based on it. The other two vitae were written in Greek. The earliest vita was composed by Theodoret bishop of Cyrrhus as part of a larger work Φιλόθεος Ἱστορία ἢ Ἀσκητικὴ Πολιτεία, conventionally called the Religious History in English. This text contains thirty vitae of Syrian ascetics, ten of whom (including Symeon the Stylite) were alive at the time when Theodoret wrote. This is remarkable—most hagiographical texts were written after their subject died, frequently a significant time after. Finally Antonius, who claims to have been a disciple who was present at Symeon’s death, wrote the third vita. Both Greek vitae are relatively short, each approximately fifteen pages long in printed editions. On the other hand the Syriac vita is nearly a hundred printed pages, more than three times the length of the two Greek vitae combined.

Although there are narrative concurrences, all the three vitae drew independently on a common body of oral tradition. Orality was certainly not a unique feature to Symeon’s vitae, indeed early Christian asceticism was very much characterized as first and foremost a living oral tradition. Although not vitae, the Apophthegmata Patrum (the conventional English name is the Sayings of the Desert Fathers) shed light on the process by which oral traditions of Late Antique asceticism became texts. These sayings and short stories—thousands of them, ranging in length from a few words to several printed pages—were written down, collected, translated, and rearranged freely over the course of generations. Oral tradition also forms part of the chain of evidence for Symeon’s sanctity. These are not appeals to ‘general knowledge’; evidence from oral tradition comes from specific often named sources, individuals whose historical activity is sometimes attested independently of the vitae. These social networks link Symeon’s miracles to specific people—other ascetics (Abba Heliodorus), priests (Mar Bas, Cosmas of Panir), bishops (Theodoret himself), officials (magister militum Ardabur son of Aspar), and even emperors (Theodosius II). Symeon’s own networks of disciples likely formed the crucial nucleus of individuals who collected and remembered stories about his life and miracles from which the three writers drew separately in composing the surviving texts.

The saint’s vita belonged to a genre of literature in which a text’s persuasive effectiveness depended on its authoritativeness. Having a famous writer, such as Athanasius of Alexandria for the vita of Antony, was one way to establish authority—the ubiquity of pseudepigraphic writings, such as the attribution of the vita of Mary of Egypt to Sophronius of Jerusalem, attests to the attractiveness of associating a text with named authority. Thdodoret of Cyrrhus was of course historically notable for far more than his biography of Symeon—he wrote theology, exegesis, an Ecclesiastical History, and played a prominent role in church politics during the ‘Nestorian’ controversy. Composed during Symeon’s lifetime and contextualizing his life as one among thirty Syrian ascetics in Theodoret’s work, Theodoret serves as a legitimating authority upon Symeon’s cult both personally as the writer and institutionally as a ranking representative of the Church. It is worth noting that Theodoret does not rely on these external sources of authority alone to buttress his narrative, but drew on logic, rhetorical skill, his own eyewitness testimony, and the oral tradition of social networks to corroborate the truth of his account.

The writers of saints’ lives were educated, intelligent people – they could read and write, after all, which automatically numbers them among the relatively small social elites of the Roman world. They could approach their subjects critically, and were conscious that their audiences, even if they were Christian believers, were rational and could even be sceptical. Theodoret of Cyrrhus makes such explicit in his opening to his account of the life of Symeon Stylites the Elder:

Now although I have the whole world, so to speak, as witness to his indescribable struggles, I feared his story might seem to those who come after like a tale wholly devoid of truth. For what took place surpasses human nature, and people are accustomed to measure what is said by the yardstick of what is natural. If something were to be said which lies outside the limits of what is natural, the narrative is considered a lie by those uninitiated in divine things. However, the earth and sea are full of devout people who, educated in divine things and taught the gift of the all-holy Spirit, will not disbelieve what I am about to write but will surely believe […]. (tr. Doran 1992, 69)

Theodoret observes that miracles are, by definition, outside of nature (φύσις), and as such will be treated as a myth (μῦθος) and lie (ψεῦδος) by non-believers. For those who will not be able to personally experience evidence of Symeon’s sanctity, either because they are removed by time (τοῖς ἐσομένοις) or by space, written accounts like this must provide evidence of his sanctity so that devout Christians will no disbelieve this story (οὐκ ἀπιστήσουσιν). Note that it is Theodoret’s words (ταῖς λεχθησομένοις) rather than Symeon’s deeds which will not be doubted – does this choice of phrase indicate the relative importance of the written medium over even the subject of its narrative? Everything contained within Theodoret’s account is true (ἀλήθεια), even as that truth is explicitly not limited by the rules of nature (τι τῶν ταύτης ὅρων ἐπέκεινα). The truth of Symeon’s miraculous activity derives directly from the reality of Theodoret’s evidence. That reality was not limited to heresay and subjective experience but integrated into the Late Antique Roman world through its social and ecological landscapes and even physical objects.

Note the presence of a rhetorical trick which serves to legitimate Symeon as a holy man and his activities. Theodoret only allows scope for disbelief for those who are ‘uninitiated in divine things.’ By establishing disbelief in Symeon as an exclusive trait for people not properly educated, he frames the impossibility for a Christian believer to doubt his stories about Symeon. After all, if a Christian disbelieves this account it must be because she or he is uninitiated and thus, by definition, not a true Christian believer. Theodoret wrote during Symeon’s own lifetime, and so his vita describes a cult which was still actively forming and potentially contestable. It may be significant that all three surviving vitae of Symeon emphasize how shocking and even repulsive contemporaries, especially his fellow ascetics in the monasteries he joined in his youth, found Symeon’s extreme self-mortification. Theodoret’s rhetorical framing effectively bestowed legitimacy on Symeon’s cult which perhaps he needed, given his extreme practices were clearly outside the previous norms for acceptable Christian ascetic behaviour.

Text, evidence and truth

The vitae of Symeon Stylites illustrate many different types of evidence cited to establish the truth of their narratives. Theodoret’s introduction starts with two, the writer (ἐγώ) and what effectively amounts to a claim of general knowledge (πάντας ὡς ἔπος εἰπεῖν ἀνθρώπους μάρτυρας). Personal, first-hand experiential knowledge of Symeon is a key narrative feature in both of Symeon’s Greek vitae.

[Ch.19] I have not only seen his miracles with my own eyes, but I have also heard predictions of future events. (tr. Doran 1992, 79)

Theodoret identifies himself as a witness to the stories involving Arab pilgrims, while Antonius, the author of the second Greek vita, inserts himself as a key actor in the events surrounding Symeon’s death and the transfer of his remains to Antioch. The veracity of these pieces of information are drawn directly from the writer’s authority, which were quite different between these two writers. Whereas Theodoret as a bishop was a leading public figure – and an accomplished theological and historiographical writer as well – Antonius’ authority was highly personal, relying on the internal claims within his text to have been one of Symeon’s disciples. Notably the compilers of the Syriac vita name themselves (Simeon bar Apollo and Bar Hatar bar Adan) without further commentary on their social identities (though we can infer that they were affiliated with Symeon’s developing cult center at Qalʿat Simʿān), relying principally on their text’s internal evidence as support for its claims. Beyond personal experience and ‘common knowledge,’ other sources which writers cite include oral tradition, physical objects, and specific geographic and topographic details as evidence in support of their stories.

It is worth noting in passing that the editors and translators of Theodoret’s text identified multiple interpolations. This in itself is not unusual for hagiography—indeed, openness of transmission is more the rule than the exception—but the insertions into Theodoret’s text adopted a style which matches the rest of the narrative, particularly the use of first-person narration. What does this do to our concept of authority? These texts of course were composed and transmitted a millennium before the invention of movable-type printing in western Eurasia. Every manuscript is a unique artifact, handmade by skilled workers at considerable expense, no two of which can be identical in the sense that we are accustomed to with printed editions. To reintroduce a now-universalized metaphor back into the subdiscipline from which it was first drawn, every manuscript is in a way palimpsest-like, inasmuch as each one is the product of unseen layers of transmission—copyists, readers, and correctors—across decades and centuries of time. In this case, perhaps the interpolations act to buttress both Symeon’s and Theodoret’s authority. These stories must have been drawn from a continuing oral tradition, and inserting them into a piece of writing legitimated them as part of Symeon’s cult. Furthermore, by inserting them into the narrative Theodoret’s own reputation would be enhanced for accurately preserving more stories remembered in oral tradition. The circularity of the logic is only apparent—or even potentially problematic—if a reader even notices the interpolated passages.

Specificity, in this case taking the form of reference to observable objects and visitable places, was a key means of authenticating information. Returning to the story of the Lion of Ukkama, a few features stand out. First is the use of a ritual practice, derived from the saint, for controlling the wild animal. Second is not just the specificity of the event with respect to location, but the tangibility of evidence for the event, in the form of a lion’s skin. This story is one of a number of miracles involving animals, itself a subset of all miracles demonstrating Symeon’s power over nature. Miracles involving wild and even mythical beasts appear in both the Syriac vita and the life by Antonius, indicating that the tradition was established early and popularly received. In addition to the lion of Ukkama, notable animal miracles in the Syriac vita also include wild goats, snakes, indescribable magical monsters on Mount Lebanon and a dragon. Stories about the last of these were perhaps the inspiration for one of the earliest suriving artistic depictions of Saint Symeon, a votive plaque from a church in northern Syria dating to the sixth century and now in the Louvre (Figure 1). Clearly these animal stories were a popular, recognizable, and legitimating facet of the successful establishment and spread of Symeon’s fame.

Bearing these types of specific evidence in mind, Symeon’s Greek life by the disciple Antonius has a few miracles with parallels to the lion of Ukkama.

[Ch.15] Hear another strange and extraordinary mystery. Some people were coming from far away to have him pray [for them] when they came across a pregnant hind grazing. One of them said to the hind, ‘I adjure you by the power of the devout Simeon, stand still so that I can catch you.’ Immediately the hind stood still; he caught it and slaughtered it and they ate its flesh. The skin was left over. Immediately they could not speak to one another, but began to bleat like dumb animals. They ran and fell down in front of [the saint’s] pillar, praying to be healed. The skin of the hind was filled with chaff, and placed on display long enough for many men to know about it. The men spent sufficient time in penance and, when they were healed, returned home. (tr. Doran 1992, 93)

The main sequence of events is even quite similar: a group of laypeople encounter a wild animal; they act out a Christian ritual connected with Symeon; the animal becomes paralyzed so that it is easily slain; its hide serves as evidence of this wondrous event so that this event becomes widely known. Although this much shorter miracle does not have the same geographical specificity, the importance of tactile and sensory evidence and the specificity of direct speech and ritual remain key features. Both writers cite the existence of the physical remains of these animals as confirmation of the authenticity of these miraculous stories. The biggest difference lies in the object of these miracles, for whereas the destruction of the people-devouring lion directly resulted in praise and thanks, the butchering of the hind brought divine punishment upon the pilgrims who did it.

The differences between the Syriac lion of Ukkama and the Greek hind go beyond just differing wild beasts, there seems to be a set of ethical consequences at play. The lion was a public danger whose ravages affected a large portion of society, and Symeon provided specific guidance for how to invoke divine power to slay it. The deer’s death only satisfied the temporary appetites of a few pilgrims, and the holy man’s name was invoked irreverently. In a text which frequently praises fasting and other forms of self-deprivation as a practice worthy of emulation, the absence of detail about the pilgrims suffering from hunger or other serious condition suggests that we should read this as not an act of desperation. This prayer tested the saint’s name for individual convenience, and it was this insolent purpose which caused divine punishment to strike the pilgrims. The story of the deer confirms the saints power both when the insolent prayer succeeded and again when the properly-chastened pilgrims were healed of their divine punishment. This reading raises an additional complication: what differentiates this insolent prayer from magic?

It is not clear how Antonius intended for readers to interpret such a story. Is this a realistic depiction of how nameless common people integrated Christian ritual into their lives which then turns into an idealistic explanation of why they are allowed to err in their practices? Pious authors keenly maintain that it is not saints themselves who possess or wield supernatural powers, but that miracles come only from God. Demons and magicians do not wield real power, they can only deceive and produce illusions. Therefore, when something supernatural occurs the source must be divine. Miracles work independently of intent or outcome. Of course the miracle did not end with the pilgrims filling their bellies with roast deer, but continued with the miraculous consequences of their actions and reactions (punishment, repentance, and eventual relief and forgiveness). Thus extrapolating from this story, if one learns of a supernatural (miraculous or magical) event which appears to be sacrilegious or otherwise counter to one’s understanding of the Christian God, then we must be missing some part of the story which explains why the supernatural event occurred.

Specific environments, universal settings

The specificity of objects and landscape—physical or social—should not be taken to imply that there are no universalizing aspects to Symeon’s vitae. The Syriac life particularly compares him multiple times with two key biblical figures, Moses and Elijah. These figures act as biblical exemplars for Symeon, and their specific choice of the two prophets involved in the Transfiguration of Jesus in the New Testament invites specific parallels between Symeon and Christ. Besides their roles as important prophets and figures in Hebrew and Christian traditions, Moses and Elijah are, of course, prominently associated with mountains: Moses with Mounts Horeb and Sinai; Elijah with Mount Carmel; and the Transfiguration is traditionally associated with Mount Tabor. Symeon’s own mountain near the village of Telneshe is a highly specific location in these texts and in the physical world would become the centre for a cult venerating Symeon after his death (Figure 2). In a way it resonates with the biblical precedents, it is simultaneously a specific and unique location in northern Syria and a representative of all holy mountains found across Syria, Palestine and Egypt.

The specific setting of Symeon’s life and miracles within the landscape of northern Syria connects his vitae with other texts from a similar time and space. Another perspective comes from the miracles of St. Thecla. Thekla was a first-century saint who is connected with Apostle Paul’s mission to Rome in the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thekla. Her miracles are a very different text, composed in Cilicia in the fifth century. Thekla’s miracles tell of her posthumous activities remembered as part of a well-established cult in the region just to the north of Antioch, and thus situated close in time and space to Saint Simeon. The following passage offers a different story set in dangerous mountainous countryside.

Our wicked and abominable neighbours [the Isaurians] sometimes pillage our lands here in the manner of enemies. … While they were fleeing [homeward after a successful raid, Thakla] confused their eyes and befuddled their brains. She turned their course back toward the East, to the plan that lies beneath her shrine, without effort and noiselessly, and handed them over to a massacre prepared by the troops. These troops, once they learned what had happened, were filled with grief and divine rage, and attacked them in the place which I noted, a place which is flat and very suitable for cavalry, and they cut the throats of all the pillagers without exception. And they accomplished this so swiftly that, from beginning to end, a single day sufficed for the massacre of many men, for setting up the victory standard, and for the return of the holy treasure and wealth to the martyr by the conquerors themselves. (tr. Talbot and Johnson 2012, 113-15)

The text tells the story of a band of brigands—hailing from the nearby region of Isauria in the Taurus Mountains of southern Anatolia—becoming lost and falling into an ambush. Like the lion of Ukkama, the miracle comes in two parts: the saint sets up the conditions for defeat upon the raiders who have wronged her cult site, but this miracle is complemented by the activity of soldiers who triumph on the saint’s behalf. In the general picture of the worldly setting and in the mechanisms by which the miracle worked the passage is comparable to the vitae of Symeon Stylites. The sort of generalized situation described in the Thekla miracle—mountain raiders pillaging, battles between them and the Roman army, the recovery of loot and prisoners, the violent fantasy of their total annihilation—will have been relatable to Late Antique audiences.

However, in sharp contrast with the attentiveness to specific details found in all three of Symeon’s vitae, this passage is sparse on particulars (πράγματα). The commander and his forces are unnamed; locations are only vaguely indicated; no date is given; no specific treasured object is indicated as having been stolen or recovered. This writer leaves it ambiguous as to whether the victorious troops were even believers in Thekla’s cult, or merely tools used by the saint. What explains the absence of specific verifiable details which would reinforce the credibility of this miracle story? It may be significant that Thekla’s cult was pan-Mediterranean, and her cult center in Cilicia made no claim to have been connected with her in life. Like how Symeon’s mountain reflected in a way the biblical landscape, Thekla’s cult was already a universalized refraction across multiple locations in the Roman world. Perhaps this hints to a difference of purpose, that the physical and social reality of Late Antique Syria was integral to the legitimacy of Symeon’s cult, whereas Thekla’s cult was sufficiently established to not need the πράγματα to get in the way of its ἀλήθεια.

It is worth briefly considering a case even more extreme than Thekla’s miracles, that being the vita of Mary of Egypt which is sometimes (and speciously) attributed to Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem (560—638). The text is almost completely devoid of specific verifiable details. Its anonymous narrator writes on behalf of the monk Zosimus, whom ‘Sophronius’ only knows about through oral tradition. The geography in Zosimus’ account is set in the literal holy land in and around Palestine, but again there is no specificity – his home monasteries have no name, and places are only vaguely indicated (Alexandria, the river Jordan and the desert beyond it). Zosimus is the only person who met with or even saw Mary, and her burial in the deepest desert ensured that there could be no geographically specific cult site to emerge around her remains. Zosimus did not even tell any of his fellow monks about Mary’s existence until after her death and burial, the point in the story when no one else could corroborate her existence. Effectively, the text insists on only an oral chain of authority without external πράγματα to confirm its details. While one might think this would have made the text less believable, that does not appear to have been the case – Mary’s vita was among the most popular in the Middle Ages and her cult spread rapidly across the Christian world. Mary’s ascetic retreat to the desert was universal because it was the desert of the holy land, the biblical setting where Jesus fasted and battled the devil for forty days, the exemplary space to which all other ascetic retreats at least partially referred. Perhaps the specificity and worldly realism of a text like Symeon’s vita just was not as appealing as a cult which seems conceived from the beginning as universal.

A final example encourages us to test the limits of what exactly we mean by the concept of ‘hagiography’, for integrated into the chronicle of John Malalas are a number of stories containing wondrous (both miraculous and magical) elements. The first part of Malalas’ chronicle was composed in Antioch some sixty to seventy years after Symeon’s death. In contrast with ascetic literature which principally drew on a living oral tradition, Malalas like other chroniclers and historians primarily relied on written sources for the information in his work. Malalas wrote a ‘universal’ history, beginning with the creation of the world, summarizing and harmonizing the biblical and Greco-Roman past, and containing an account of recent history up his present. This final part principally focused on his home city of Antioch and neighboring regions. This portion of the chronicle bears a striking resemblance to a genre of ancient literature about the history of cities, called patria. As a patria for the city of Antioch, Malalas’ chronicle contains multiple stories about wonderous and unnatural events which occurred in or around the city over the centuries of Late Antiquity. One miracle in Book 17 (covering the reign of Justin) stands out for its parallels with the other examples previously explored. It is an account of an earthquake which struck the city of Antioch during the festival of Easter in the spring of AD 525.

Some of the citizens who survived [the earthquake and fires in the city] gathered whatever of their possessions they could and fled. Peasants attacked them, stole their goods and killed them, and strangers robbed them and stole from them. … But God’s benevolent chastisement of man was revealed even in this, for all those robbers died violently, some by putrefaction, some were blinded and others died under the surgeon’s knife, and after confessing their sins they gave up their souls. One who plundered at that time was called Thomas the Hebrew, a silentarius, who had escaped in flight from the wrath of God and lived three miles out of the city at the place known as St Julian’s Gate, and, by means of his servants, stole everything from the fugitives … . He did this for four days, and as he was polluting everything he suddenly died though he had been in good health and strong, he collapsed and died suddenly, before he had even compiled an inventory of all that he had plundered. And everyone who heard of this glorified God, the rightful judge. His property was dispersed by the elders, and some of it was stolen and lost so that he had nothing left but the robes he wore. He was buried there, in the place where he died and in that robe, for fear of the citizens who were clamoring against him. Other mysteries of God’s love for man were also revealed. … (tr. Jeffreys, Jeffreys and Scott 1986, 238-40)

Earthquakes – here called the wrath of God, wonderous events in the most horrific possible sense of the concept – were and are common to the Eastern Mediterranean, which today we understand is a region where several continental tectonic plates meet. This passage tells of now-familiar dangers facing refugees fleeing into the countryside, namely brigandage and death. Even without the intervention of a saint though, God still ultimately administers just punishments to wrongdoers both generally and to Thomas the silentarius specifically, reinforcing the same worldview as we fine in the lives of saints. Notably, Malalas utilizes a familiar set of rhetorical tools, reinforcing general wonderous truths by referencing specific verifiable details: dates, persons, places, and of course consequences. Despite being a different genre according to modern taxonomic classification schemes, there does not seem to be much to differentiate the thought-world of John Malalas from that of any of Symeon’s hagiographers.

Perhaps the thought-world, the world as it existed in the collective imaginations of the people who inhabited Late Antique Syria, joins social networks and the physical environment as a vector for our understanding of the past. The depiction of landscapes in hagiography reflects social attitudes about what constituted ‘realistic’ settings, which contain both mundane and miraculous elements. The parallels with chronicles and patria (which were not persuasive literature) shows that these settings were culturally internalized and repeated outside of the hagiographical contexts in which they formed. For authors and readers alike, wonderous claims – be it of miracles, magic, or disasters – required evidence and persuasion.

Conclusion

The vitae of Symeon Stylites the Elder are highly specific with respect to time, social environment, and physical geography. This precision of space and time serve a specific function within the text, providing external confirmable evidence for the truth of the account. At the same time, the texts set down an otherwise oral tradition in such a way as to preserve memory of events which occurred in specific spaces associated with Symeon’s cult – both those proximate to Telneshe and those much further away. In a sense, space serves story as much as story serves space. Does the particularity of the evidence make the contents of this text more useful as a historical document than texts without such specificity? Is Symeon’s mountain holy from its specificity or holy because it is a mirror for the other mountains associated with Moses and Elijah? The spiritually beneficial truth of this text is still grounded in the repetition of biblical forms and precedents which characterize works which are set in an unspecified space-time, like the stories of St Mary of Egypt (or Barbara) which are devoid of chronological or geographical specificity. The study began by examining how landscape serves as a framework for understanding evidence in hagiographical sources, examining it in terms of society, environment, and specific tangible objects. In the end, it may be that there is another type of landscape, the thought-world which exists in the collective imagination of the people who inhabit it. Like hagiographies themselves, it is not strictly factual in a mundane sense which historians are trained to find satisfying. It is built on such πράγματα of course but comprises imaginative and even wonderous elements as well. Any discrepancies in details between the various types of landscape found in these sources from Late Antique Syria – social, physical, conceptual – do no diminish the collective ἀλήθεια for those who dwelt there. Realism in this context might just be the literary reflection of a sort of collective imagination.

January 16th, 2023 by DC Whalin